04 Nov The Himologan Settlement: Prehistoric Cagayan and How it Almost Became Part of Maguindanao

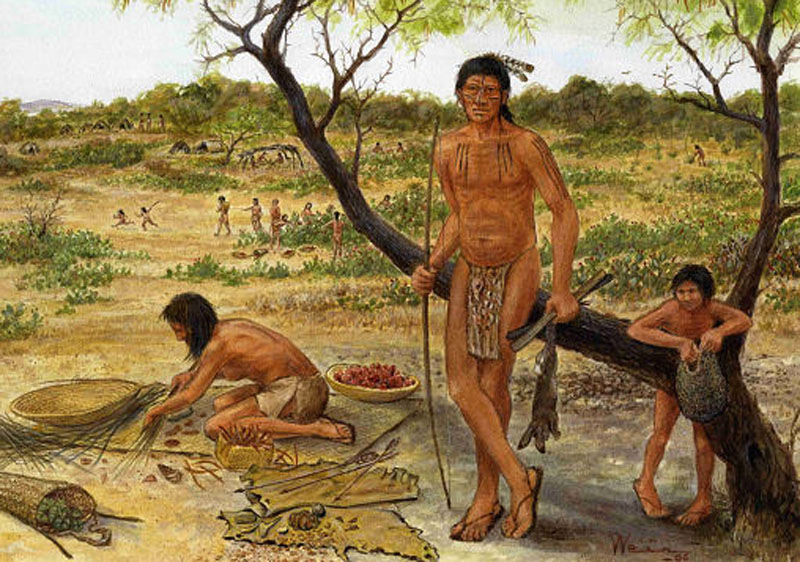

In a previous article it was pointed out that the early inhabitants of Cagayan and Mindanao did not come from “waves” of migrants from the Malay and Indonesian lands, but rather, from migratory trickles from many places. It was also established that aside from these different migrants there were already local natives like Negritos and Bukidnons that already inhabited the mountainous regions. Also, local migrations from the hinterlands, the Visayan Islands, and Butuan eventually would contribute to the establishment of Himologan along the banks of the Cagayan River.

According to Roland Burrage Dixon in his book, Peopling of the Pacific, and Fay Cooper Cole, an anthropologist from the University of Chicago, Illinois, USA, since it has been an accepted and proven fact that both migrants and local inhabitants in the Philippines were nomadic in nature, it was only natural that these nomads would explore almost the whole of Mindanao whether along the shorelines or following water sources into the interior. After hundreds of years of nomadic exploration, it was only typical that many settlements or tribes would have been established, examples being the principalities of Butuan, Lanao, and Maguindanao as well as separate settlements in Camiguin and Cagayan (Himologan).

Huluga and Himologan

From the many studies done in Cagayan, especially in Huluga and its surrounding areas, it is clearly established that the early inhabitants in the caves of Huluga were nomadic Negritos and Bukidnons who through the years simply followed the rivers, streams, and tributaries that led towards the Cagayan River. It was only natural that the early settlers in Huluga that found the caves considered this a good fortune because of its close proximity to the river and yet commanded a promontory (high ridge) with a line of sight to the surrounding areas, affording both freedom of access to the river as well as security.

According to local studies conducted by Antonio J. Montalvan II, Mardonio M. Lao, and Fr. Francisco Demetrio, S.J., to name a few, nomadic movements from other places would eventually discover the Huluga settlement, with resulting trading and intermarriages that followed. As the Huluga settlement began to grow, it would expand outside of the caves and would eventually become the early Cagayan settlement we know of as Himologan.

Archeology in and around the Huluga area has already attested to varying evidence ranging from material culture to human remains, many of which are now on display in the various museums around the city. When the archeological digging sites and artifacts were sent for carbon dating to the National Museum of the Philippines and by Dr. Linda Burton to the University of Chicago, dating revealed that Huluga already existed as early as the late Neolithic Age, around 3000 B.C.

Other dating reveals timelines up to 1565, thus, proving that Huluga existed from the late Stone Age while Himologan ushered in the Iron Age era in which its inhabitants began agriculture around the plains of Himologan while doing mining in the gorges in and around the area of what we now call as Macahambus.

All this proves therefore that Huluga and Himologan were one and the same area and inhabited over a long period of time starting from around 3000 B.C. up to around 1565. This is considered Cagayan de Oro’s Prehistoric Age.

Proof and Evidence from the Spaniards

According to Fr. Francisco Demetrio, when the first Spaniards first stumbled on the Himologan settlement, they found a mixture of Negritos, proto-Manobos, Bukidnons, and Visayans, though the main language being spoken was Visayan. These early Cagayan people already had their own language, their own folklore, subsistence system and patterns, dress, religion, dance, culture, and even writing.

Fr. Demetrio further surmised that the lack of written records from prehistoric periods wasn’t because early Filipinos could not write; on the contrary, both spoken and written language already existed in this prehistoric period. However, unlike Europeans who had perfected the art of paper and parchment making, as discovered in China, so documents can last longer, early Filipinos did not discover parchments until long after the Spaniards brought it with them. Thus, early writings were done on thin bamboo strips or threaded dry leaves that unfortunately disintegrated over time. Also, the limited trading done by our prehistoric forebears with Chinese traders did not yield any exchange that included paper.

Himologan Almost Became Part of the Maguindanao Kingdom

At its peak, Himologan numbered more than 500 intermixed people, and as what was normal during that period, the settlement did some trading with the principality of Butuan. It was from Butuan that there was limited trade contact with Chinese traders due to continuous Chinese and Siamese ambassadors visiting Butuan. There was also some trading with the principality of Cebu, but the biggest trading partner of Himologan was with the principality of Lanao. In fact, before the Spaniards arrived, Himologan was under the rule of Datu Samporna from Lanao. Later when the Spaniards Christianized the Himologan natives, the Samporna clan was given the new Christianized family name of “Neri.”

However, from the later part of the 1400’s up to the 1500’s, Islam missionaries began to spread the Islamic faith and began converting whole principalities and kingdoms. Many of these missionaries themselves became the rulers such as Sultan Kabungsuwan of Maguindanao.

Around the late 1500’s, Kabungsuwan heard about Himologan from his Lanao subjects, and so sent an Islam missionary, Sharif Alawi to convert the settlement. The natives however, resisted this change to their religion. After so many years, Kudarat’s father, Sultan Bwisan, decided to just extract tribute from Himologan. Because of its small size and the fact that they could never resist such a large kingdom, the rulers of Himologan decided to pay continuous tribute to the Maguindanao kingdom rather than face its armed invasion.

Thus, in the end, though Himologan became a tributary to Maguindanao, it never became part of that kingdom and its inhabitants were never converted to Islam. This resistance to Islam conversion and the eventual stopping of tribute payments would anger future rulers of Maguindanao and Lanao, enough to launch attempted invasions of the settlement. What they did not realize was that by the time this happened starting in 1622, Himologan was already a protectorate of the Spanish flag, and it was the priests who ordered tribute payments to stop. But as they say, this is another story.

No Comments